- The Meat Paradox

- The Identifiable Victim Effect

- Why the „Cattle Sympathy“ Campaign Failed

- What the Best campaigns Get Right

- The Role of Marketing in Change

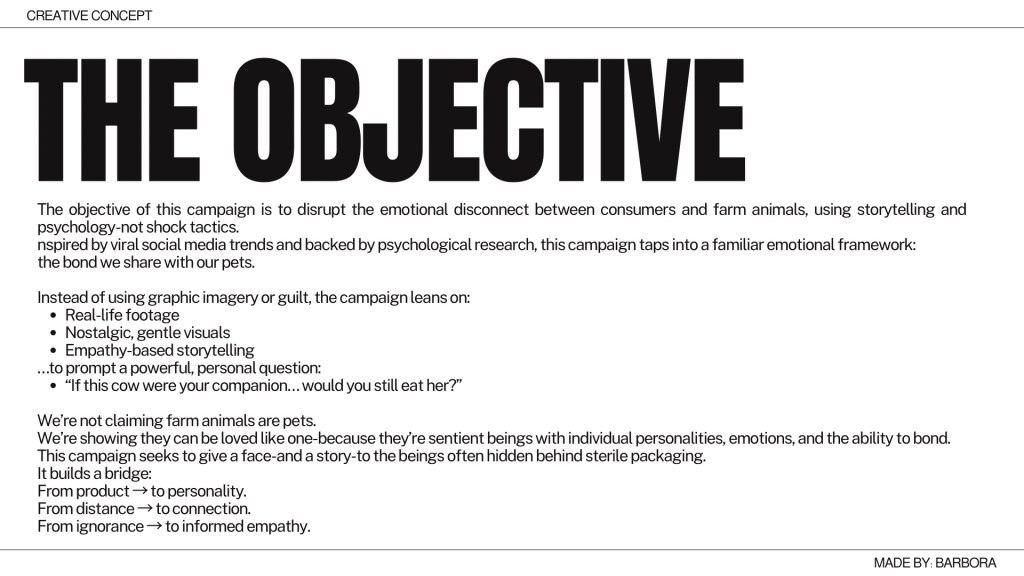

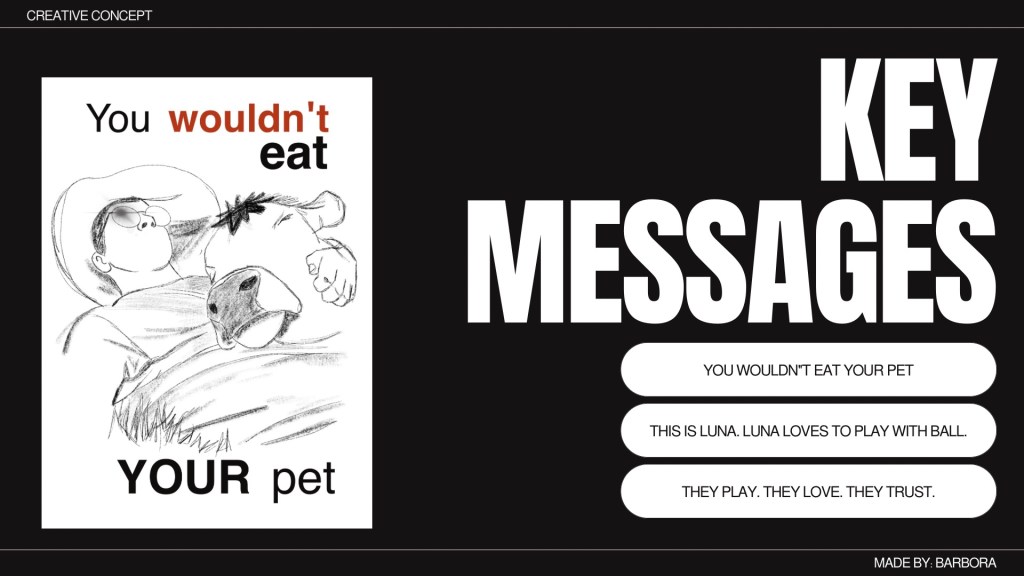

- CAMPAIGN CONCEPT – „You wouldn’t eat your pet“

In today’s world, we’re seeing the rise of devoted pet parents. We give our pets birthdays, names, and sometimes treat them like toddlers. We often attribute human emotional and behavioral traits to our animals, to our pets. This strengthens the human-animal connection, expresses empathy, and shows our care for their well-being. This phenomenon is formally known as anthropomorphism (Caviola, Kahane, 2021).

Recent research supports the idea that many animals experience a wide range of emotions – including fear, joy, compassion, rage, and even grief and shame (Suer, 2021). Dogs, cats, elephants, penguins, primates – and yes, cows, pigs, and chickens – all display emotional complexity. Cows and pigs are especially intelligent; pigs, in particular, have been shown to outperform toddlers in certain problem-solving tasks (World Animal Protection, 2023). Cows form strong social bonds and exhibit emotional awareness (Arrowquip, 2023). Chickens have friends, recognize faces, and display empathy within their flocks (The Humane League, 2023).

The Meat Paradox

I dare to argue that we, as humans, love animals. And yet, we still harm them – we eat them. Many of us have seen documentaries showing the horrors of factory farming and slaughterhouses. It’s an awful picture of animal suffering, driven by humanity’s hunger for meat.

This contradiction is known as the meat paradox-the internal conflict between caring about animals and consuming them. It’s often explained through cognitive dissonance – the psychological discomfort of holding two opposing beliefs at once. To avoid that discomfort, we mentally separate „meat“ from „animals“, treating them as if they exist in two different realities (Caviola, Kajane, 2021). I dare to argue that we, as humans, love animals. And yet, we still harm them – we eat them. Many of us have seen documentaries showing the horrors of factory farming and slaughterhouses. It’s an awful picture of animal suffering, driven by humanity’s hunger for meat.

Marketing plays a huge role in reinforcing this dissociation. Animal products are packaged and presented without any hint of the living being they once were – no eyes, no blood, no fur, no story: just polished packaging and appetising labels. Consumers are conditioned to see meat as “food,” not as a sentient being. The more disconnected the image, the less we think about animal suffering. This contradiction is known as the meat paradox-the internal conflict between caring about animals and consuming them. It’s often explained through cognitive dissonance – the psychological discomfort of holding two opposing beliefs at once. To avoid that discomfort, we mentally separate „meat“ from „animals“, treating them as if they exist in two different realities (Caviola, Kajane, 2021). I dare to argue that we, as humans, love animals. And yet, we still harm them – we eat them. Many of us have seen documentaries showing the horrors of factory farming and slaughterhouses. It’s an awful picture of animal suffering, driven by humanity’s hunger for meat.

The Identifiable Victim Effect

Another psychological pattern relevant here is the Identifiable Victim Effect – our tendency to feel greater empathy and provide more support for a single, named individual than for a large, vague group (Kogut and Ritov, 2005).

Put simply, we care more about “Baby Jessica” stuck in a well than statistics showing thousands of children starving. It’s not rational – it’s emotional. The more visible and emotionally relatable the individual is, the stronger the reaction.

Why the „Cattle Sympathy“ Campaign Failed

In this case study, I don’t argue whether meat consumption is morally right or wrong. It simply is. But what I aim to explore is how empathy can be activated when we humanise animals – by giving them a name, a face, a story. By turning animals from products into beings.

One activist protest, known as the “Cattle Sympathy” campaign, involved stamping beef packaging with the names of slaughtered cows. The intention was to make people stop and think – but instead, the campaign backfired. People treated it like Coca-Cola’s “Share a Coke” labels, even buying meat that had their own name on it. Jokes like “I’m eating myself today” or “Gotta collect all the cow names like Pokémon” flooded social media.

So why did it fail?

1. Lack of story

A name alone means nothing. Humans are narrative-driven-we need a face, a backstory, an emotional hook. “Sofie the cow” is not enough. Who was she? What did she love? Did she play with kids? Without context, there is no connection-and no empathy. This ties directly to the Identifiable Victim Effect (Kogut and Ritov, 2005).

2. Cold, sterile packaging

The campaign used a minimal stamp – “RIP Bella” on a plastic-wrapped steak. It didn’t evoke sadness-it evoked irony. People laughed, got confused, or ignored it. This speaks to cognitive dissonance and dissociation – the meat is already separated from the animal in consumers’ minds (Caviola and Kahane, 2021).

3. No emotional or visual cues

Compare this with successful campaigns like Amarula’s elephant conservation project, where customers named elephants and had those names printed on liqueur bottles. That worked – because people saw the elephant, named it, and felt emotionally invested. The packaging became part of the story. It had a face, a name, and a cause. This is anthropomorphism used effectively (Foxpak, 2022).

What the Best campaigns Get Right

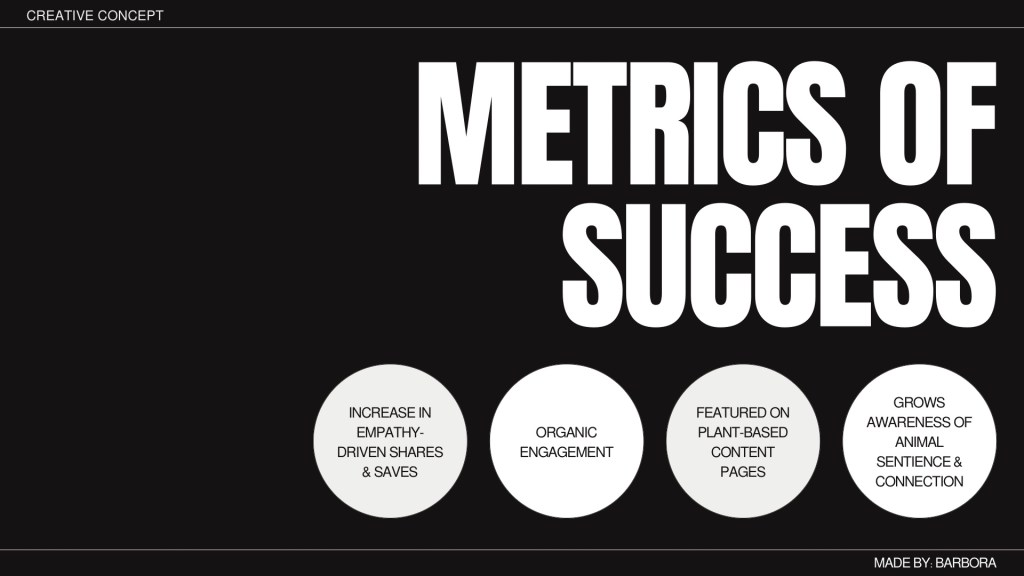

Campaigns like Amarula, Chewy’s „What’s In A Name“, or Oreo & Friends succeeded because they built empathy bridges. They gave people a role – a way to participate, a name, a face, and a story. These are the exact psychological ingredients that the „Cattle Sympathy“ campaign lacked.

The Role of Marketing in Change

When we look at the patterns above – the dissociation, the meat paradox, the power of narrative-we realise marketing is not just a tool for selling. It’s a tool for transforming beliefs.

If we can change how animals are portrayed – if we present them not as statistics or packaged products, but as individuals – we might help people reconnect. If we show one animal at a time, give it a story, and treat it with the same love we treat our pets – we can reduce consumption, raise awareness, and foster respect.

And this is exactly what inspired the campaign I’m about to present – a concept born from scrolling through TikTok, where I saw cows playing like dogs, chickens cuddling their owners, and even people attending cow therapy sessions. It made me think:

“These aren’t products. These are pets. These are beings.”

So I started designing a campaign – scalable, emotionally grounded, and built to activate empathy – one cow, one pig, or one chicken at a time.

CAMPAIGN CONCEPT – „You wouldn’t eat your pet“

Although the idea originated from publicly available TikTok content, the framing, messaging, visual identity, and analytical insights presented here are entirely developed by the author.

The drawings included in this case study are hand-drawn interpretations of the themes observed in TikTok content. They are not reproduction of the videos themselves but creative reinterpretations developed for this case study.

The sources below include academic/scientific and cultural inspirations (e.g. TikTok content). The later are cited to acknowledge the spark of inspiration rather than as scientific evidence.

Arrowquip (2023) ‚Cattle Are More Emotional Than You Think‘. Available at: https://arrowquip.com/blog/animal-science/cattle-are-more-emotional-than-you-think/ (Accessed: 18 September 2025).

Caviola, L. and Kahane, G. (2021) ‚Moral Intuitions About Animals: Speciesism in Everyday Life‘, Social Psychological and Personality Science. Available at: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6940846/ (Accessed: 18 September 2025).

Čížkovská, B. (2025) You Wouldn’t Eat Your Pet – campaign poster series. Original digital illustrations created for portfolio use. Not publicly published.

Foxpak (2022) ‚The Benefits of Personalised Packaging‘. Available at: https://www.foxpak.com/flexible-packaging/personalised-packaging-benefits/ (Accessed: 18 September 2025).

Kogut, T. and Ritov, I. (2005) ‚The „Identifiable Victim“ Effect: An Identified Group, or Just a Single Individual?‘, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15534510.2016.1216891 (Accessed: 18 September 2025).

Krishna Cow Sanctuary. (n.d.). Videos of cows interacting with humans and showing pet-like behaviour [TikTok profile]. TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@krishnacowsanctuary?lang=en

Pubity. (2024). Viral video of girl raising a pet chicken [TikTok video]. TikTok. https://www.tiktok.com/@pubity

OpenAI ChatGPT + DALL·E (2025) AI-generated image of a middle-aged couple shopping for meat in a supermarket, generated via prompt by B. Čížkovská, 19 September 2025. Created using ChatGPT and DALL·E. Not publicly published.Pubity (2024) ‘Rooster follows girl like pet chicken – emotional bond’ [Video]. TikTok. Available at: https://www.tiktok.com/@pubity/video/7446593628257963296 (Accessed: 19 September 2025).

Sueur, C. (2021) ‚Empathy in Animals: Scientific Evidence and Human Attitudes‘, University of Western Australia. Available at: https://online.uwa.edu/news/empathy-in-animals/ (Accessed: 18 September 2025).

The Humane League (2023) ‚Do Chickens Have Friends?‘. Available at: https://thehumaneleague.org/article/do-chickens-have-friends (Accessed: 18 September 2025).

World Animal Protection (2023) ‚Do Pigs Feel Emotions?‘. Available at: https://www.worldanimalprotection.org/latest/blogs/do-pigs-feel-emotions/ (Accessed: 18 September 2025).

Napsat komentář